Note: This presentation provides further pictures and commentary for our Dubrovnik overview. It's best to see that presentation first by clicking here.

| You may prefer to see these pages as a photo slide show which contains the same text but presents the pictures full screen size. If so, click on the slides presentation at the right -- or click here. |

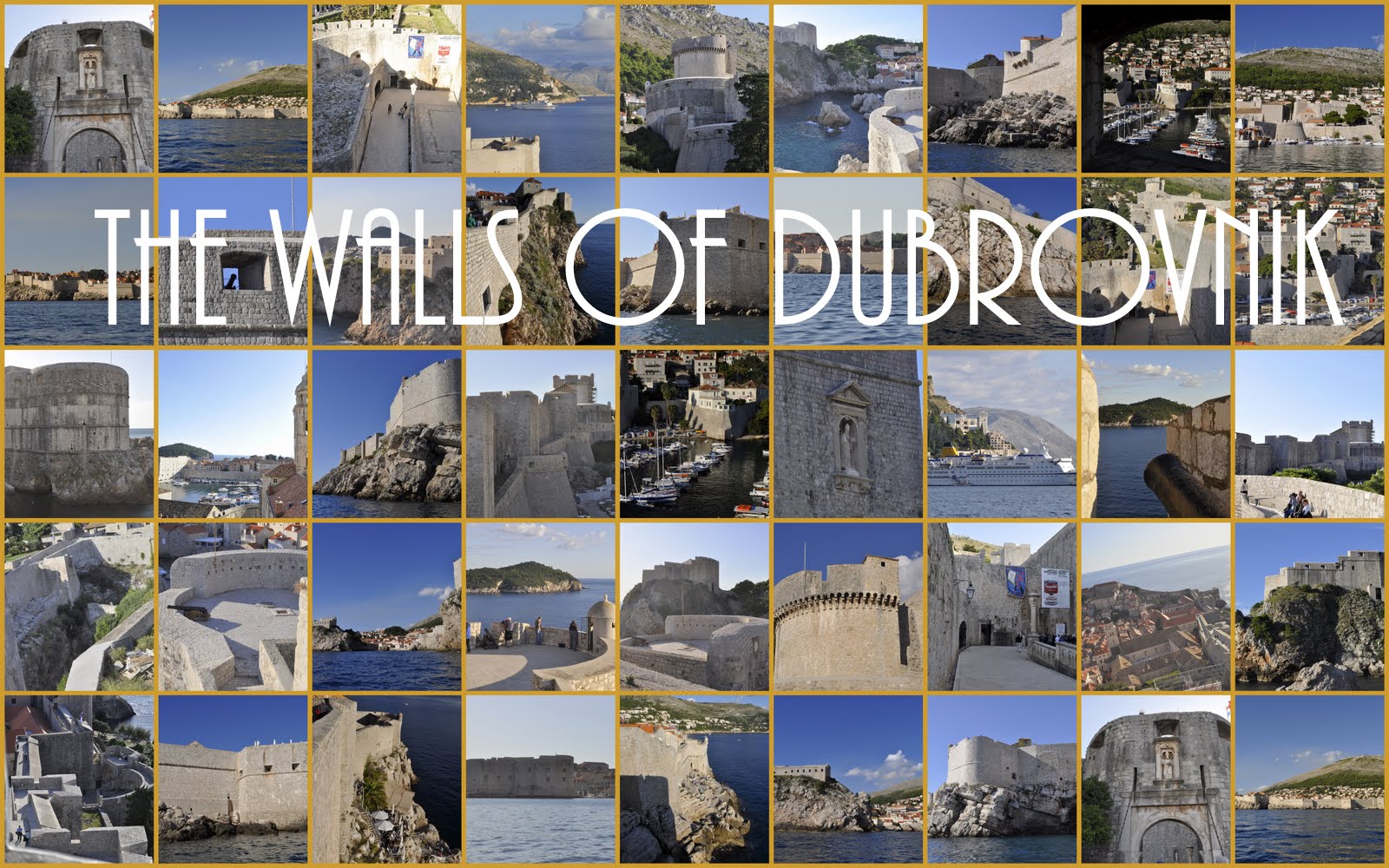

Day or night, by land or by sea, Dubrovnik's walls are highly visible

as one approaches this historic city. One of the strongest set of

fortifications in Europe, these were never breached. The town fell only

once, when that rascal Napoleon and his buddies were invited in to help

defend -- and decided to stay and take over the place. (Oh, those

French!) But to a large degree, Dubrovnik's best defense were the

skillful diplomats who played the city'-states's enemies off against

each other such as the Venetians and the Turks. (Diplomacy sometimes

consisted of paying tribute -- and bribes -- to each of those countries

as well.) At the rear we see the Croatian coast -- only about 4 miles

wide at this point. Over these mountain lies Bosnia and Herzegovina --

land of the Ottoman Turks until 1878

Here's another view: the dark green blob was for four centuries the

Ottoman's westernmost province: Bosnia, which hovered just over the

mountains from the skinny republic of Dubrovnik shown in magenta. Pale

green Venice encroached with its string of islands and shoreline

colonies creeping like a snake on the northeast shore of the Adriatic.

For citizens of tiny Dubrovnik, good fences, and diplomacy, make good

neighbors. (Thanks to the University of Texas for putting this map into

the public domain.)

These walls were a long time abuilding and today are superbly

maintained and make for a pleasant walk. These replaced previous

defenses and were built and rebuilt from the 11th to the 14th centuries

as the city expanded. The Turk threat starting in the 15th century gave

Dubrovnik, like much of southern Europe, a strong incentive to further

fortify their defense, especially on the land side. Work continued into

the second half of the 17th century. Here we climb towards the most

significant land defense, the Minčeta Tower. Note in the background we

see a lower wall -- it's separate from the original wall and is meant

to take the hit of an artillery attack while keeping the tower defenses

intact. It's known as a scarp wall.

Here's an outside view of the stone wedding cake known as the Minčeta

tower -- the design of one of Florence's most famous Renaissance

architects: Michelozzo di Bartolomeo Michelozzi, builder for the

Medicis. As a sculptor and collaborator with Donatello, Michelozzo did

subtlety. But as a defensive architect, he did force as well. When both

Constantinople and Bosnia fell to the Ottomans in the mid 1400s,

Dubrovnik knew it had to strengthen the town's highest spot owned by

the Mincetic family. They invited Michelozzo to design this and several

other fortifications. He placed this round middle section with 20-foot

walls above the existing 4-sided fort built in 1319 and integrated it

into the scarp walls.

Here's a southwestern view of the Minčeta tower which should be called

"the sculptor's tower". This utilitarian structure was created by

master sculptors of both the Renaissance and Gothic eras. After

Michelozzo, work continued by a Venice-trained sculptor and architect

from the Croatian city of Zadar named Juraj Dalmatinac (or in Italian,

Giorgio da Sebenico.) Dalmatinac was not quite the Renaissance man like

the Florentine Michelozzo. He's best known as a medieval sculptor and

his masterpiece is the Gothic cathedral (and UNESCO World Heritage

site) in his home town of Šibenik where, incidentally, he received the

greatest homage a sculptor can get: Ivan Meštrović created a sculpture

of him in front of his masterpiece cathedral.Construction completed in

1464 -- since then it has been a symbol of the impregnability of

Dubrovnik.

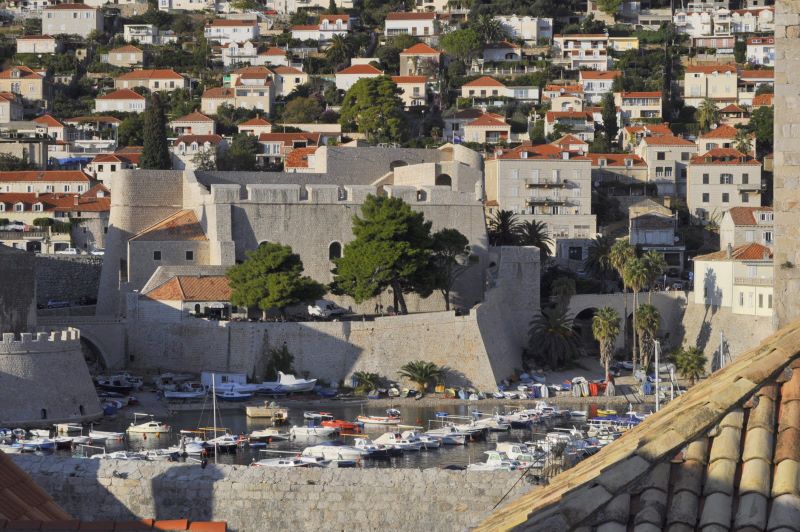

A small harbor sits as the western ends of the town and it's protected

in the distance by both a stand-alone fort called St. Lawrence

(Lovrijenac) and, in the foreground, by another round Michelozzo

fortification extending from the city walls called Fort Bokar.Military

builders' mantra was that architects win more wars than generals.

(Since warfare in those days consisted primarily of parking an army

outside a walled city and trying to convince it to surrender, they had

a point.)

The smaller harbor (called Kolorina) is protected by St. Lawrence

Fortress (Lovrijenac) at left and the Bokar cylindrical tower at middle.

Rising over 100 feet above the sea, St. Lawrence Fortress (Lovrijenac)

appears impregnable from both land and sea. Venetians tried to build

their own fort here in the 11th century. Had they succeeded, Dubrovnik

would have been their colony. Dubrovnik beat them to the punch,

erecting a fort in three months -- in time to greet the ships laden

with construction materials arriving from the thwarted Venice. The

present footprint dates from the 14th century but it was modified in

subsequent centuries including after the 1667 earthquake that

devastated Dubrovnik.

Built triangular in shape to fit its rocky underpinning, Fort Lawrence

(Lovrjenac) is known as Dubrovnik's Gibraltar. The rock base is not

level -- creating the need for the three terraces we see here. (Today

these terraces make a great backdrop for the Summer Festival's staging

of "Hamlet.") The sea-side walls are very thick -- nearly 40 feet thick

-- to resist the enemy cannons...

...but the land walls are much thinner -- less than 2 feet. Why? The

Dubrovniks feared that their commander --elected from the nobles for a

1 month term -- would use this dominant position to take over the town.

So they constructed the walls that faced the town thin enough to blow

apart, if need be. (They also only provisioned the site for 30 days at

a time). Trust, but verify!

Protecting the eastern end of the small harbor across from Fort

Lovrijenac, Michelozzo's Fort Bokar (foreground) rises from the

Adriatic -- a masterpiece of defensive architecture. Michelozzo was

brought to Dubrovnik to help rebuild the walls and he commanded a huge

salary as an expert on city wall fortifications, having worked

throughout Tuscany. (Obviously his work in Florence has been torn down,

but his work at Lucca still stands.) He was considered a master at

engineering. And he was not a second class artist: Most of the big

architectural names of the Italian Renaissance did fortifications

including Brunelleschi, Leonardo, and Michelangelo.

Look carefully at the two levels of holes. This is a casemate (or

casement) meant to protect canons. Michelozzo's cylinder is both

elegant and functional -- and perhaps presages the gun turrets which

would eventually adorn battleships and tanks.The Bokar citadel and th

Minceta tower suffered serious damage during the 1991 bombardment.

Town leaders were in a hurry to get Fort Bokar built and condemned

several houses nearby to provide building materials and to provide

additional free space. Completed around 1462, it now hosts events for

the annual Dubrovnik Summer Festival. But when built, it was meant to

protect the major land entrance into the city...

...the Pile Gate which today still holds its drawbridge although the

moat below is now a landscaped garden. This is still the primary land

entrance into Dubrovnik, a city which takes understandable pride in its

walls. Here again we have a cylindrical tower (built in 1537) providing

both beauty and function. These visitors pause on a double-arched

Gothic bridge (built 1471) by Paskoje Miličević Mihov, a town native

famous for his work on these walls and those at a nearby area called

Ston where Dubrovnik controlled the lucrative salt trade. (Stay tuned).

Well, not quite a cylinder -- but it does sport a Renaissance arch and

a statue niche. The wooden drawbridge was lifted each night as part of

an elaborate ceremony. It replaced a late 14th century stone bridge.

Note the second statue inside the bulwark. Citizens were taking no

chances at this critical entrance.

interesting juxtaposition (top-a-position?) of Saint Blaise and cannon.

Must be a symbol of a just war (or, perhaps, just a war.)

Here's a close-up of the Renaissance niche with the town

patron/protector St. Blase, holding a model of his city. He looks a bit

unhinged here between the arrow niches. Perhaps he played in the NFL

before their new concussion policy went into affect.

To the left is the Renaissance rounded front; behind is the older Pile

Gate area with its winding Gothic entrance to avoid a direct frontal

attack on the walls. We look north here as the city rises to its

highest point at the Minceta tower.

While the exterior of Pile Gate is Renaissance, the interior is Gothic

and completed in 1460. Both city gates cause visitors to wind through

several defensive areas (in case they are bringing battering rams).

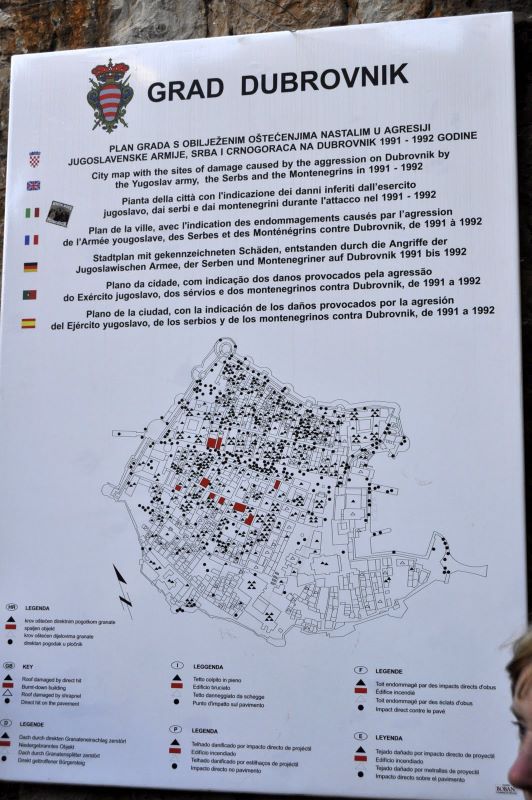

Just inside the gate, Dubrovnik reminds its many visitors of the

devastation caused by the 1991 assault by the Yugoslav army as they

attempted to capture Dubrovnik from Croatia and give it to Montenegro.

Over 650,000 shells hit the area with more than 1,000 landing inside

the city walls where over 250 people died. The marks show where shells

hit in this UNESCO World Heritage site with no military targets. (Over

2/3rds of the buildings took a hit.) Dubrovnik's location far from the

major portion of Croatian territory made it difficult for her defenders

to obtain assistance from their countrymen. Serb attackers shelled the

city from the mountains above and the sea around it after cutting off

food and electricity. Water was rationed inside at 1.2 gallons per day.

(If you have an efficient American toilet, you use 1.6 gallons per

flush).

Here we look southwest from the Pile Gate towards the Bokar fort as

these thick walls hover over their moat (now a garden.) The land walls

are typically 12-19 feet thick -- and strong enough to survive the 1667

earthquake that devastated most of Dubrovnik. At center we see a square

tower -- 1 of 15 built during the 14th century. The lower portion is

the scarp wall. These walls held even during the 2 month onslaught of

the modern Yugoslav army in 1991. Supposedly artillery had made castle

walls meaningless long ago -- but Dubrovnik stayed impregnable as it

has since these walls were built.

Here's another southwest view from higher up where we see the rounded

exterior of the Pile gate and more square projections.

This shot of the north side shows the scarp wall. Cars have taken over

what was once the moat. The scaffolding at center rear is on the

Minčeta tower.

This view of the northern section of Dubrovnik was taken from the

Minčeta tower which now protects a basketball court -- a big sport in

the former Yugoslavia. (The Croatian star Dražen Petrović was

considered to be the man who started the flood of Europeans into the

NBA before his untimely death at age 28.)

Looking southeast from Fort Minčeta -- Clockwise: old port and St. John

Fortress at 9 o'clock; Lokrum island at and the cathedral spire (in

scaffolding) at noon; the Jesuit church shows its Gothic side at 1

o'clock.

But there's no moat like the sea. The clever elders of the city gave a

strip of land between Dubrovnik and Venice to the Ottomans -- thereby

eliminating the path for of a land attack from Venice. At that point,

the city concentrated on defending from an attack by sea. This came

back to haunt Dubrovnik during the 1991 siege when their fellow Croats

could only provide support from the sea.

The sea walls range from 5-10 feet thick. The walls extend completely

around the city (about 1.2 miles) and once sported over 120 defensive

cannons -- cast in Dubrovnik's workshops.

Walls rise above impressive sea cliffs.

In the distance is the Fortress of the Passing Bell -- named after a

nearby church bell rung when people died. It's also the design of

Paskoje Miličević Mihov who did the stone bridge at the Pile Gate --

but was built much later from his plans.

These rocks may provide better defenses than the walls themselves.

The city rises on hills behind the walls. Here we see the Jesuit church

(left) and the cathedral (scaffolded dome) rising above the eastern

walls as we near the port.

Another view of the walls which seem to grow organically from the sea

cliffs.

Here we looking south towards the island of Lokrum on one of the 3

circular towers.

Somehow a restaurant has managed to set up shop in the tiny area

clinging to the sea wall.

Today assaults from the sea come from cruise ships -- a welcome change

for Dubrovnik which gets the lion's share of its income from the

tourist trade. We were to see much more of this spectacular shoreline

where mountains abruptly end at rocky shores.

The old port, of course, is way too small for such ships. Here we see a

smaller ship which will offload passengers just as we in Houston

offload our crude from tankers too large to enter our ports.

Guarding the southern end of the old harbor, St. John's castle (also

called Mulo Tower) also contains museums, an aquarium, and restaurants.

It's another design by Paskoje Miličević Mihov which shows several

cylinders to the sea but is flat on the port side.

Here's a view of the flat side of St. John's fortress and the island of

Lokrum beyond. The tower is part of the Dominican Monastery which was

originally outside the walls (and therefore had to be heavily fortified

before a later expansion of the walls would envelop it.)

Looking north across the harbor. In the middle ground is the Dominican

Monastery which resembles a fortress from the outside (left over from

the days when it was outside the walls). At right is a bridge leading

to the second city gate (Ploče) and extending to the stand-alone

Revelin Fortress.

Here we look from St. John's fortress north towards the Revelin

Fortress, built around 1580 as the Ottoman Turks threatened. It's the

design of Antonio Ferramolino, a military architect from Bergamo. For

11 years no other construction was allowed so that all resources could

focus on fortifying this point with all deliberate speed. A chain would

be suspended between these forts to the breakwater (called "Kaise") at

right to keep out enemy ships during time of siege.

Another view of Fort Revelin: Like Fortress Lawrence (Lovnjenac), this

was a detached fort and protected the east gate to its left in this

picture. As at the west gate, a double arched bridge leads across the

moat into the city. This fort was also protected by a moat on the

opposite side -- making it an island. It survived the 1667 earthquake

that damaged most of the city.

These west end of the harbor holds these three arches (a fourth at left

has been blinded). These were the arsenal where ships were built or

repaired. To lessen the chance of sabotage, these arches would be

bricked in while the ships were repaired. This area also held the

warships used to defend the city -- but only a few as Dubrovnik armed

most of its merchant fleet. Today it's a coffee house.

At the north end of the harbor we find the Romanesque eastern entrance

called the Ploče Gate. Simeone della Cava built this mid 15th century

and it was widened in the 19th century.

In this view we look back at St. John's fortress and the once powerful

harbor which is now a marina. (The modern port has moved to a larger

area nearby.) From this port, Dubrovnik's 180 merchant ships sailed

from the Black Sea to London and mediated trade between the Balkans and

the rest of the Mediterranean.

Above is one last picture. These are Dubrovnik's walls but are not in

the

city itself but were key to defending it as they protect the narrow

isthmus leading into the peninsula of Pelješac which Dubrovnik acquired

in 1333. These are the walls of Ston and claim to be the second longest

in Europe (after Hadrian's walls -- see our presentation on them by

clicking here.)

These were about 4.5 miles long when built in the 15th century (with 40

towers and 5 fortresses). The dots in the water are of cages used to

farm seafood. Ston itself was the center of the salt production for the

region and perhaps has the oldest salt planes in the Adriatic area.

Someday there may be a near bridge here. If so, it will connect all of

Croatia now separated by the tiny projection of Bosnia Herzegovina into

the Adriatic.

|

Please join us in the following slide show to give Dubrovnik Defensive Walls the viewing they deserve by clicking here. |

Geek and Legal StuffPlease allow JavaScript to enable word definitions. This page has been tested in Internet Explorer 8.0, Firefox 3.0, and Google Chrome 1.0. Created on January 12, 2010 |

|

See our other Dubrovnik pictures by clicking here