[

During

the last years of his life, Francis worked with Dick to fill in the

gaps of his biography. Dick's comments and additions are in brackets

such as this.]

Dim Prospects

Francis graduated from St. Augustine's in Kalamazoo in June

1931 in a class of 25 of which only 4 were left in 2003 when this was

written).

[However, with the advent of the depression,]

Francis’s education stopped with the move to Cork Street; all worked to try to make ends meet.

Martin was a prized tenant farmer because he had a wife and three teenage sons. [

Tenants

shared the crop with the landlord per negotiated terms and so both

shared profits and losses. However, before the recession, Martin

had changed this arrangement and, instead, was paying cash rent instead

of sharecropping.]

The Depression started in 1928. Francis became aware of the

depression in 1931 when his family was unable to keep its commitment to

the $200 monthly cash rent for the Sprinkle Road farm. Vern

Gilbert (who owned a farm on Cork Street) offered his farm a mile away

to the family. Cork street was tenant farm. This move was

from the Sprinkle house with electricity and running water to the Cork

house with neither!

[However, the electricty then supported few of the conveniences we have

today.] Sprinkle road had a 12 volt Delco gasoline motor-driven

generator which charged a bank of probably 12 batteries enclosed in

glass so you could see the bubbles as they charged. These

provided current to both house and barn but worked only for lighting

(no refrigerator).

Meat Before Refrigeration

A typical dinner before refrigeration would almost always include potatoes. [But how would you preserve meat?]

Pork: A

pig would be butchered when cold weather started. (Outdoor

refrigeration would cool the meat). An uncle, Mathias Banner, was

an authority on butchering. (He remembered this from Germany).

When the pig would be butchered, the family would have the liver

(considered a treat) that day. The intestines would be stripped

to be used as casings for sausages. The family had a smokehouse

(usually near to the outhouse so they would look like twin

smokehouses). Hickory wood would be used for the smoking which

was a type of preservative and flavoring for the meat. As the

weeks would go by, Emma would partially cook the ham on the wood stove,

and put it in a 10 gallon crock, and then pour melted lard over it to

seal it. This would keep into the summertime. The family

would peel off a layer of ham to eat, and the remaining lard would form

a seal. This was one of the main sources of meat.

Sausage would be made from the pig. It was probably put in 2

quart jars sealed with melted lard; the mason jars would then be sealed

when they were hot. As they cooled, an airtight seal would

form. If the preservation was not correct, you could see seepage

out of the jars. This happened only occasionally.

Uncle Mathias would make head sausage (ingredients unknown) from parts

of the pig’s head. Pig hocks would be used in sauerkraut.

(Cabbage would keep in the cellar for a while).

Beef: usually the family would get a quarter of a cow from someone. It would be cold packed

(packed in jars and boiled on the stove; then sealed with rubber rings;

a vacuum would form as the jars cooled.)

Beef would be prized

when threshing crews came as threshing was a neighborhood

cooperative project. [Threshing was a process used in the

harvesting of grain which is typically done today by large farm

machinery.] As many as twenty people would compose a

threshing crew. The lady of the house would be responsible for

the preparation of the noon meal and sometimes the evening meal.

Threshing was in the hot summer days of July and August and depended

upon good weather. Grain had to be dry to thresh properly.

Sometimes we would thresh into sunset.

Labor was done like a barter system; Probably farmers kept track of the

number of hours and teams of wagons and horses. Five or six teams

would be required to keep a threshing machine busy.

Chickens: Typically the family

would get 100 day old chicks from

Zeeland, [a nearby town]. These would be packaged with enough

food to last until they would arrive at the purchaser's farm.

They’d come railway express in a cardboard box

(approximately 2' by 3' by 6 inches tall) with holes in the

sides. You could hear the chicks peeping. Out of the 100, a

good caregiver could raise 98 to adulthood. The chicken’s were

Emma’s

responsibility. They’d be fed daily with grain (often corn, home

grown and cracked at the mill). Purina also made chicken feed

fortified to encourage growth.

Chickens were usually of one of two types: white

leghorns (smaller and good layers) or

Plymouth rocks (larger, beefier, speckled gray.) Their primary

use was to have fresh eggs. Hens would be good layers for a

certain number of months. When they stopped laying, they’d become

chicken dinners, usually on Sunday.

[Dick recalls Emma adroitly beheading a chicken for one such dinner.] Sometimes a hen would sneak

off and lay eggs (7-10) and set on them. It took 21 days for eggs

to hatch. (Emma would usually have a rooster who’d announce the first

stroke of light).

The eggs were the property of the lady of the house. They were a

source of food and could be taken to the grocery store and exchanged

for groceries. (There were also friends and relatives who would

come to the house to pick up eggs).

Breakfast was usually oatmeal, often with raisins. Francis's mother had

to hide the raisins as her boys cherished them as a snack. She

would move them often, but they were usually found. Francis

doesn’t remember his mother complaining of the diminishing supply of

her raisins.

Side dishes

[The tenant contract would allow for a side garden where the family could grow vegetables to maintain themselves.]

Other vegetables in winter besides cabbage would be carrots. In

addition, Emma canned all summer long, such as green

beans and tomatoes. Food would be preserved by canning while root

vegetables (potatoes, squash, and carrots) would be kept in the cool

basement.

Uncle Mathias Banner would have a contract with a pickle company with

storage vats in Mendon along the railroad tracks. He’d grow a

half or whole acre of pickles. The little pickles were worth the

most per pound. Bigger ones lesser. The dill size were

worth even less. When the vats would be filled, the company would

stop buying. The unpicked pickles grew even larger and eventually

were picked and stored in thirty-gallon wooden barrels of a salt-water

brine with dill to become a winter’s supply of dill pickles.

Martin’s family would take their share home in batches. (Pickles

were non-nutritious and you needed cider vinegar to make them.)

Lighten up

The

Rural Electrification Act (REA) moved electrical wires down country

roads. REA was one of the good things Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR)

promoted; it changed rural America, putting its people on a par with

city people. Cork Street got its first electricity.

The first thing farmers would get when their house became electrified

was a refrigerator so they could have cold drinks and preserve fresh

food. Emma’s [Francis's mother] refrigerator was a Crosby Shelvador (so called

because it was the first to have shelves on the refrigerator

door). Before this, the family did not even have an ice box.

Electricity came to Cork Street Farm about a year after the family

moved there. One of the neighbors wired for lighting. Most

importantly, electricity was put in the barn; the family switched from

a hand cranked one cylinder engine to an electric motor-driven

milker.

Electricity in the house was a godsend with the lighting and

refrigeration. The refrigerator and radio were the only

appliances. Electric iron and washing machine soon

followed. (Before that, you’d have a small gas engine to run the

washing machine; before that, hand operated). Before electricity,

the family used kerosene and gasoline lanterns and lamps. Coleman

company came up with lamps with fragile mantles like those used in

camping today). A special type of gasoline was required.

Typically the glass lampshades of kerosene lamps and lanterns would

need daily cleaning. Every day Emma would trim the wicks and

refill the lanterns with the smelly kerosene. The white gasoline

was much cleaner and smelled better.

[The family probably got its first]

phone around 1917 (before electricity). These were low wattage

with party lines. Each house had a separate ring with 2 to 8

houses

on a single line; you couldn’t tell who was listening in.

The Stove

The kitchen always contained a wood-burning stove with a reservoir to

heat water. (Probably a 5-10 gallon reservoir) for bathing and

washing. A fire box (usually on the upper left side) was the heat

supply and there would be separate doors for the oven. The stove would heat the kitchen

(including overheating in the summer before electricity brought in

fans).

The farm cook was really and experienced engineer, to control the

proper heat for baking and the various temperatures required for

stove-top cooking. Above the stove were two warming ovens heated

by the stovepipe as it passed through (see photo below).

Usually

the family ate in the kitchen. A formal dining room would be used

for company. The farms always had wood lots. Usually enough

wood would be cut in the winter for the whole year. Farmers had

more time in the winter and wood split more easily.

Living rooms would contain a heating stove burning wood or hard coal or

coke. Some stoves had

Isinglass so you could see the fire.

Isinglass

[a type of mica] could withstand the heat. If the economy was good

enough to buy coke or hard coal, the keeper of the fire had an easier

time. Removal of ashes from all stoves was a daily chore that

could be messy.

The Economics of the Cork Street Farm

The Gilbert Farm on Cork street had a larger dairy herd (as many as

sixty milk cows) since it was bigger; so life revolved around the dairy

heard. Gilbert was a more aggressive farmer and knew more

about marketing. He owned the Cork Street farm but would lease

anything available. He was a good businessman who lived in

Kalamazoo. He also bought and sold horses.

The Gilbert farm on Cork street was the family’s most productive farm

and Martin and Emma stayed there more than 20 years until they

semi-retired to Otsego. All refuse was returned to the

land. The wheat grew so tall that rainstorms would flatten it,

making it difficult to harvest. The family had a small (5 foot)

combine pulled by a tractor with a power takeoff (a way of transmitting

power through universal joints). Stanley would be the most clever

operator given his natural agility.

The family grew wheat, barley, and oats as a cash crops and corn (for

silage and grain). Oats were a favorite grain for the horses.

[When interviewed in 1995 for a

profile for the Journal of the Michigan Dental Association, Francis

discussed his family's situation in 1931:

"I was cultivating corn and this man

from the implement dealer came out with my dad to where I was

working. My dad said, 'Let him have the tractor.' That was a

beautiful John Deere machine and it was important to our

livelihood. I knew then that things were tough."

Read the rest of that interview by clicking here.

Later on we would find out from

relatives that they were using tractors that Francis had purchased for

them. He never told us.]

During this period, wheat could fall to below 33 cents/bushel (less

than the production costs). Some farmers burned wheat in lieu of

buying coal.

|

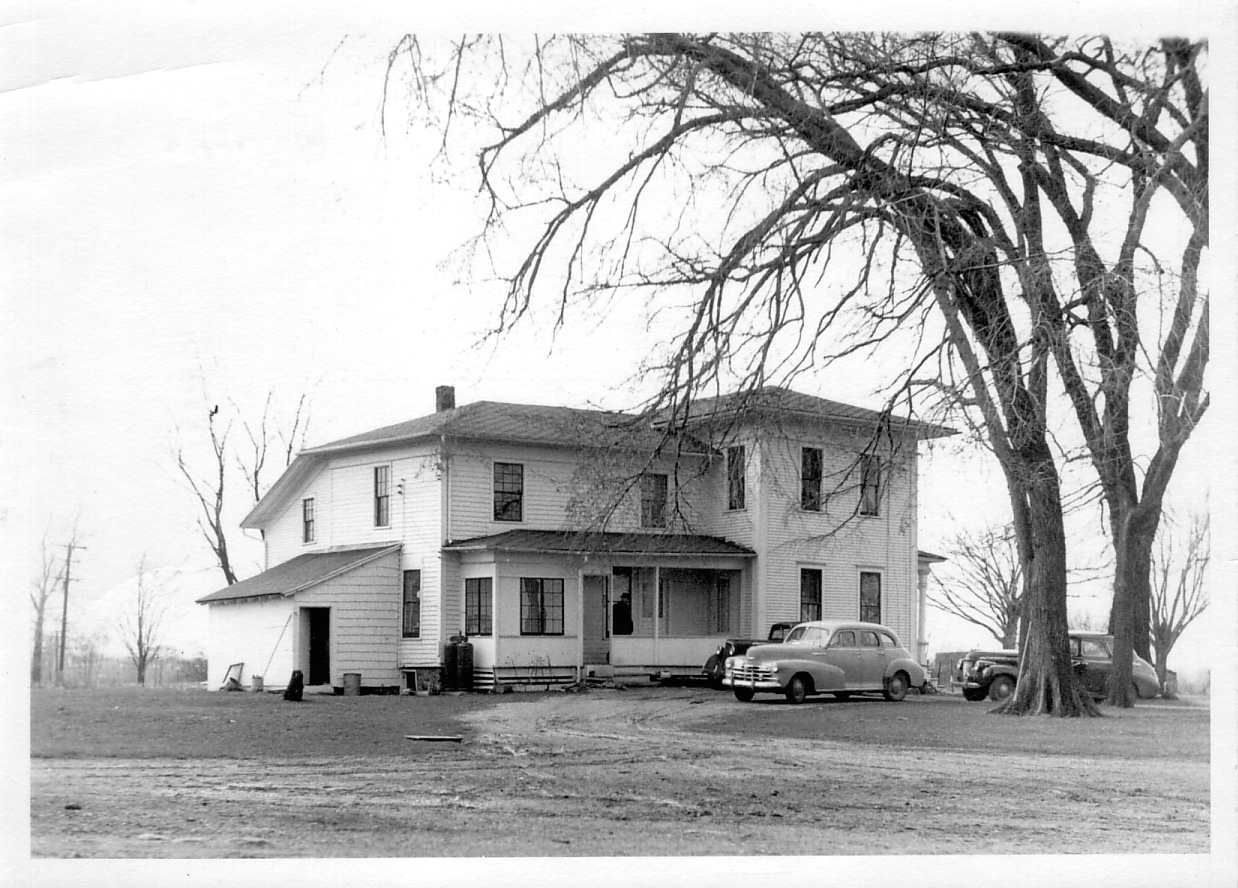

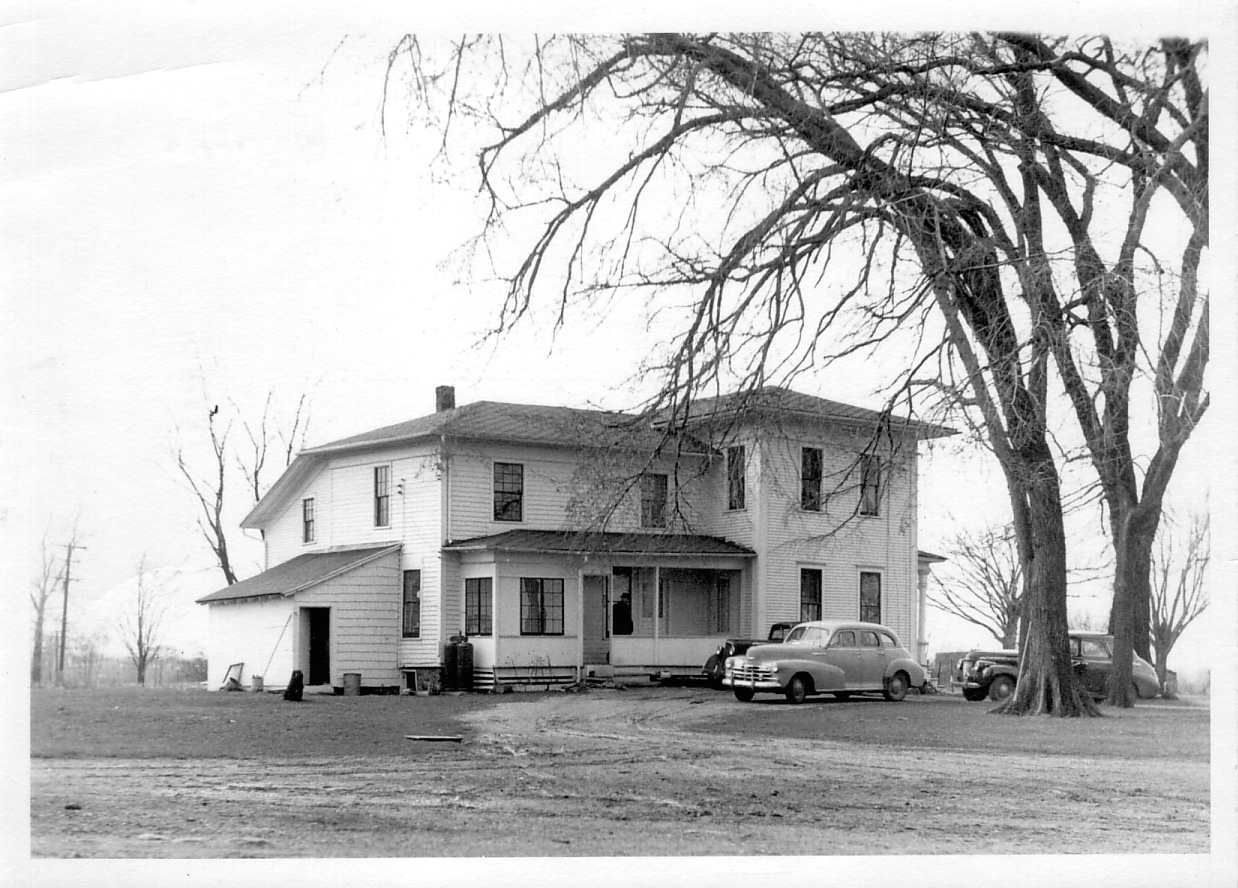

We

would travel often to overnight at the Cork Street Farm until it was

sold in the early 1950s. (l to r): Tom, Mark, Dick, Paul with

Emma and Martin in the back row.

|

On the farm, the family would follow the work of the seasons.

Planting in the spring, harvest in the summer and fall, and feed the

animals (cows, horses, and mules) forage and grain during the winter

months.

Life was on hold during this time. Gilbert graduated a year after

Francis in 1932.

After graduation, the boys would mostly be marking time. Both were work hands on the farm. Days

would start at 4:30 AM to collect the cattle from the pasture; followed

by milking the cows, cooling the milk, and taking it to the creamery in

a Ford Pickup truck (model T). During school days, they’d drop

the milk off at the creamery on the way to school and pick up the empty

cans on the way home. Then they would help with the milking; do

their homework, and go to bed to start the next day all over again.

A truck could pick up the milk on a route, but usually the Schmitts had

enough milk to more cost effectively bring the milk in

themselves.

The milk market was falling apart as well both from over production and

from under consumption by the public who didn’t have enough money

during the depression to buy milk.

|

October, 1936: After

preparatory work at Western State Teachers College (now Western

Michigan University) but before obtaining a bachelor's degree, Francis

enrolled in dental school at Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI. He is seated on the right in this freshman class photo. (per Tom)

|

The Accidental Dentist

In July 1934, an event happened that changed Francis’s life.

During haying season, he fell from a ladder climbing into a hay mow (a

storage place for hay). He has no recollection of the accident

but probably fell 15 feet. He was taken to Borgess Hospital where

he came to some days later. The diagnosis was a fractured left

wrist; from what he now knows, possibly a fractured skull. His

cousin, Lawrence (Larry) Banner, the family physician, told Francis’s

parents that he wouldn’t be able to do physical labor for at least 3

months. Someone suggested that Francis start back to school at

Western State Teacher’s College (now Western Michigan

University).

Larry Banner was a double cousin, about 8 years

older than Francis and somewhat of a mentor to him. Larry Banner had studied Dentistry at Marquette for one year before

switching to Loyola Medical School. He suggested to Francis that

he become a dentist. Another mentor was the local dentist, Dr.

Morrison M. Heath, a Marquette grad. Francis would work summers

in Dr. Heath’s office when he was going through Dental school.

Heath was a very successful denture maker in Kalamazoo. In these

days before the emphasis on preventive dentistry, many people lost

their natural teeth early (eventually everyone, if they lived long

enough). Heath

showed Francis how to set up teeth in the making of dentures.

Francis’s goal at Western was to get his preliminary subjects out of

the way before admittance to dental school. This typically took

two years. Francis attended from 1934/35 through 1935/36.

While at Western, Francis met James Dillon, a farm boy from Paw Paw,

Michigan, probably at the Western Neumann Club [

A ministry for Catholics at state schools.] He came

home with Francis several times where he met Lucille. The rest is

history (and eleven surviving children).

|

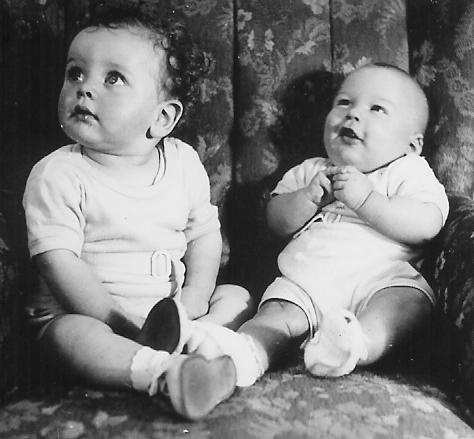

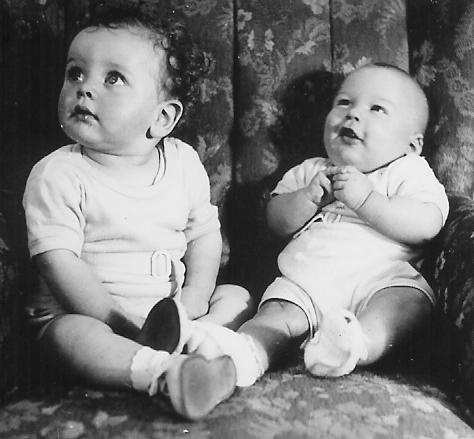

For their families, these are

rare only children -- at left the child of Jim Dillon (Jimmie), the

first of 11; right the child of Francis (Tom), first of 12. This

picture was probably taken at Fort Bragg, NC, in 1944.

|

Francis started Marquette University Dental School in Milwaukee in Fall

1936 where he graduated in June 1940. Dr. Heath helped Francis

financially the last two years. Francis never knew from one

semester to the next if he’d have enough money to stay in school.

His parents helped as much as they could. He borrowed some from

Vern Gilbert and Morris and Eleanor Heath. He’d work summers at

Dr. Heath’s office and on the farm. In those days, $100 was max

earnings for a summer.