The Civilian Community (Vicus)

Visited 20 March 2006

The Civilian Community (Vicus)Visited 20 March 2006

|

|

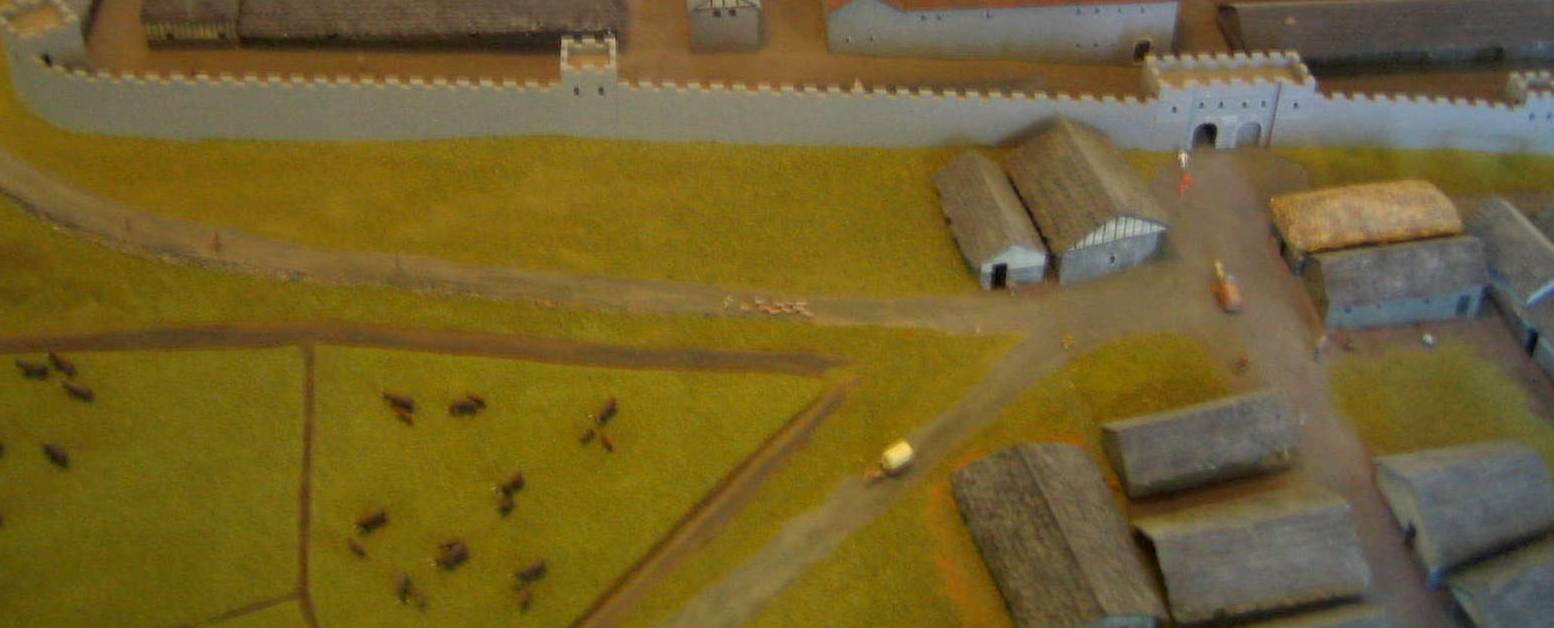

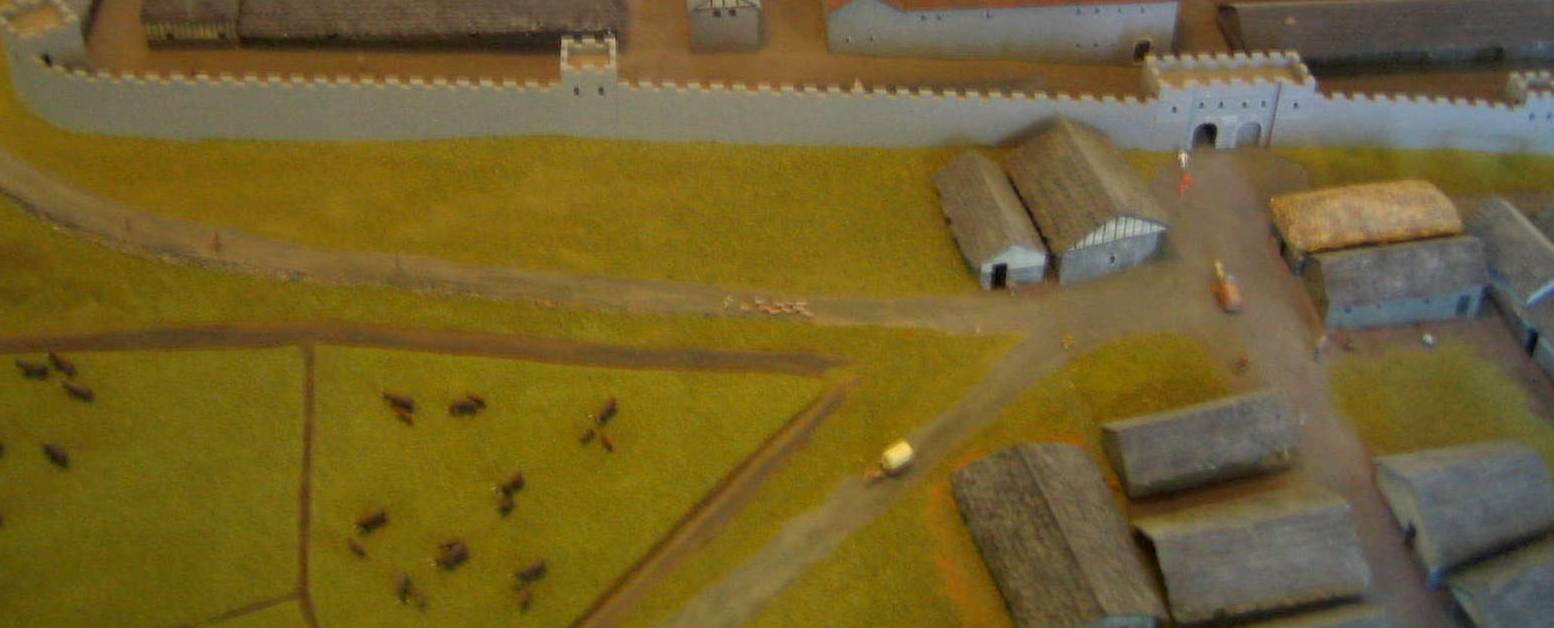

To serve the needs of the soldiers, the garrison town (called a vicus, which means "row of houses" in Latin) sprung up and eventually extended south of the fort from the east gate westward. The picture below shows some of these on the southeast side at left. Somewhere between here and the car park (which would be out of the picture to the far left) would be the site of the first town, Chapel Hill, which should be called temple hill. These included shrines to Jupiter, Mars Thincus (a Germanized version of the war god Mars probably brought here by the Belgian tribes that staffed the fort) and Mithras.[48]

Mithras started as the most important Iranian god and evolved to be the Roman god of mutual obligation between the emperor and his troops. The worship of Mithras, seen through the filters of Plato and containing rituals for baptism and the sharing of bread and wine, was a late development in the aging Roman pantheon. It swept through the troops quickly, perhaps increasing their chances of promotion. Its ascent roughly coincided with the rise of Christianity in the empire. Interest in Mithras died out when the Emperor Constantine, no stranger to this area, converted to Jesus. As we've found in the 21st century, religious rites were important to the religious right, if you were on the right side. After Constantine, Saint Michael became the patron of soldiers and the temples to Mithras were literally converted to his name. The Vatican itself was built over a mithraeum.

|

So far, over 20 buildings (6 currently showing) have been excavated in the Vicus as far as 200 yards from the fort.[34] What were these used for? Of course, there were the obvious housing needs for those supporting the fort (enlisted men could not have wives -- at least not in the fort. When the auxiliary troops retired, they received Roman citizenship for themselves and one wife -- go figure). Also, the soldiers received part of their pay in cash giving rise to saloons, shops, and what discreet guide books call "other places of entertainment." It also appears that, unlike most forts in this area, part of the garrison was housed outside the fort.[48]

Romans encouraged their ex-soldiers (granted citizenship on discharge) to stay in the garrison and intermarry with the locals. This eventually created a local population loyal to Rome.

|

The civil settlement first started at Chapel Hill but by the end of the 2nd century had moved to the fort's shadow. Hadrian would not have liked that as he wanted fort borders clear so they could be more easily defended.

|

The vicus did not always reflect its well-ordered fort and more was going on than worship of gods. A counterfeit coin press has been found here as well as the "murder house" where two skeletons were excavated beneath its floor, one with knife fragments in his ribs.[35,36] (Side note: the fort museum was built to the footprint of the "murder house" to provide a sense of scale for visitors that can be difficult to derive from the remaining piles of stones.)

Housesteads appears to have died with a whimper, not a bang. Rome could no longer support its far flung provincial forces after AD407 and this area was not capable of supporting the large population of the fort through agriculture.[49] The place disappeared from history (along with so much else) during the dark ages. It lay outside the civilized world, too north for England and too south for Scotland, a rough place seemingly beyond the reach of law until 1698 when the infamous gang of Armstrongs sold out and moved to America.[50] . Apparently those colonies had lax immigration policies even then. (Maybe they should build a wall to solve that problem. Have them call M. Maginot if they're not ready to go to war with the wall they've got.)

Shortly thereafter, the excavations started, culminating in the Housesteads inclusion acquisition by the National Trust in 1974.

![]()

This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.