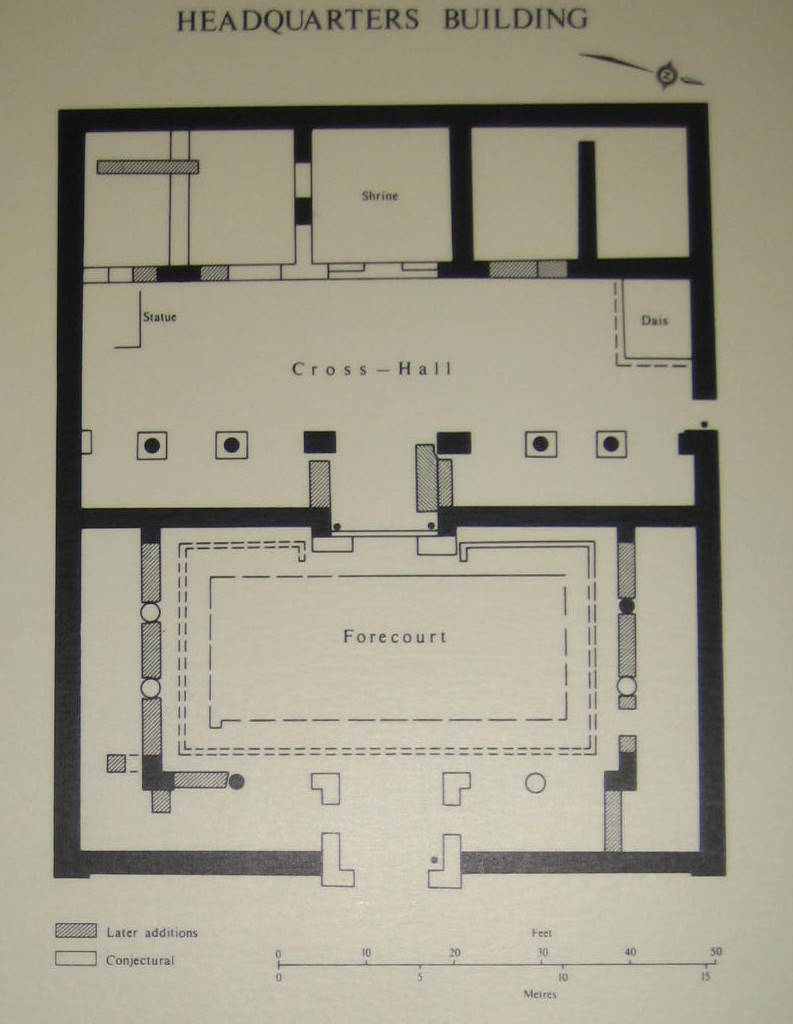

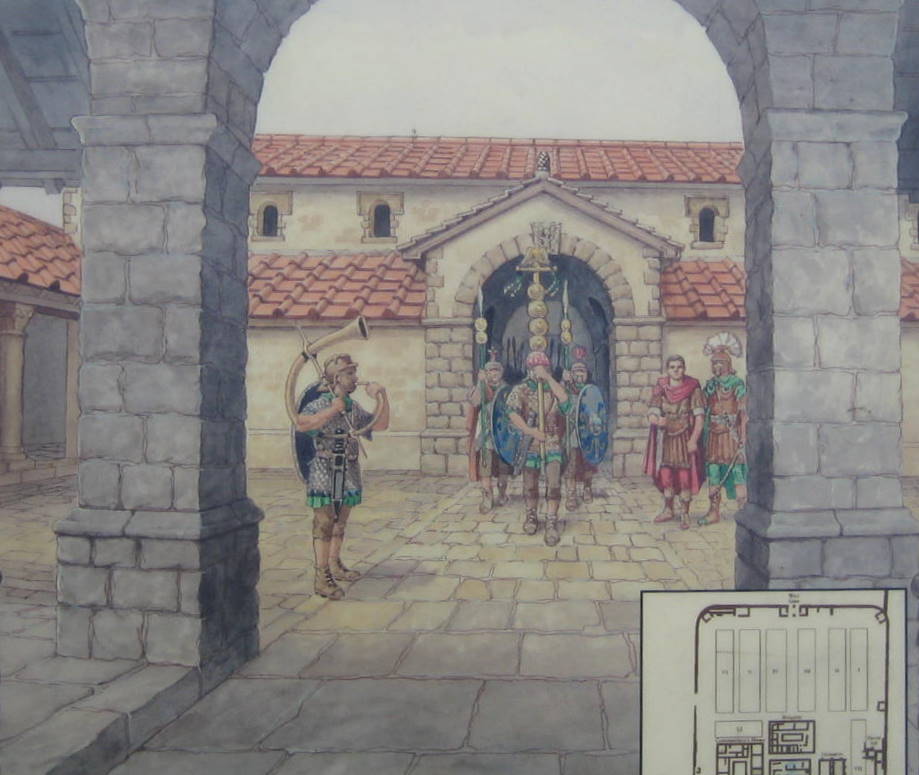

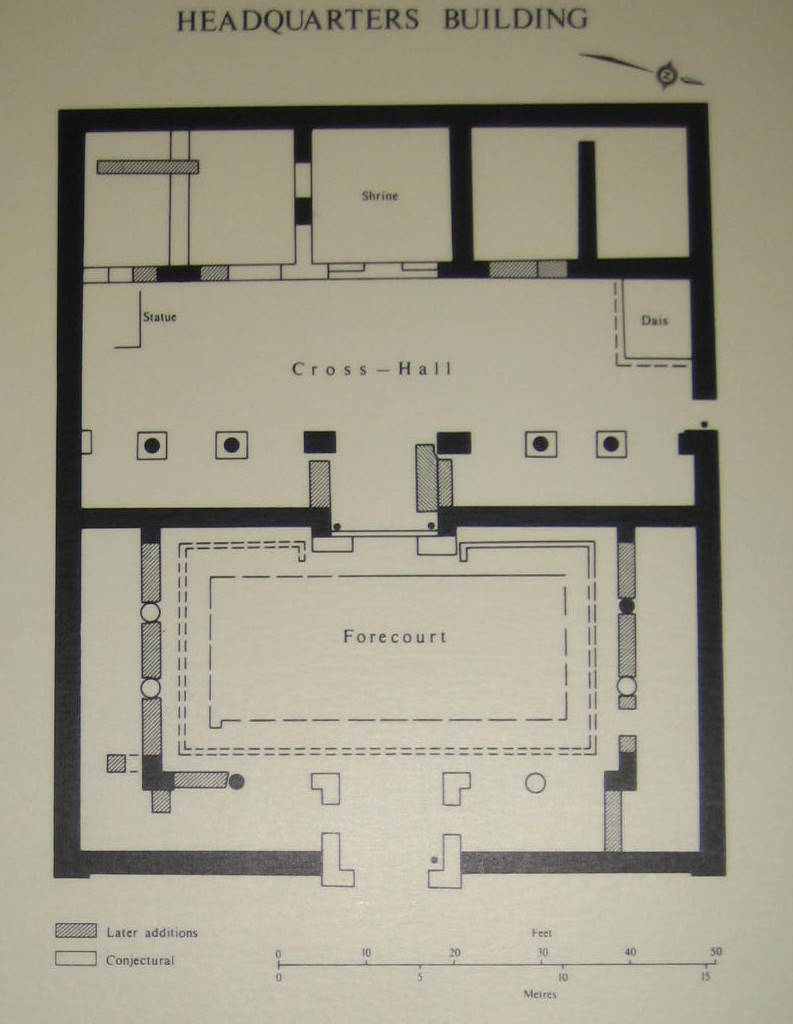

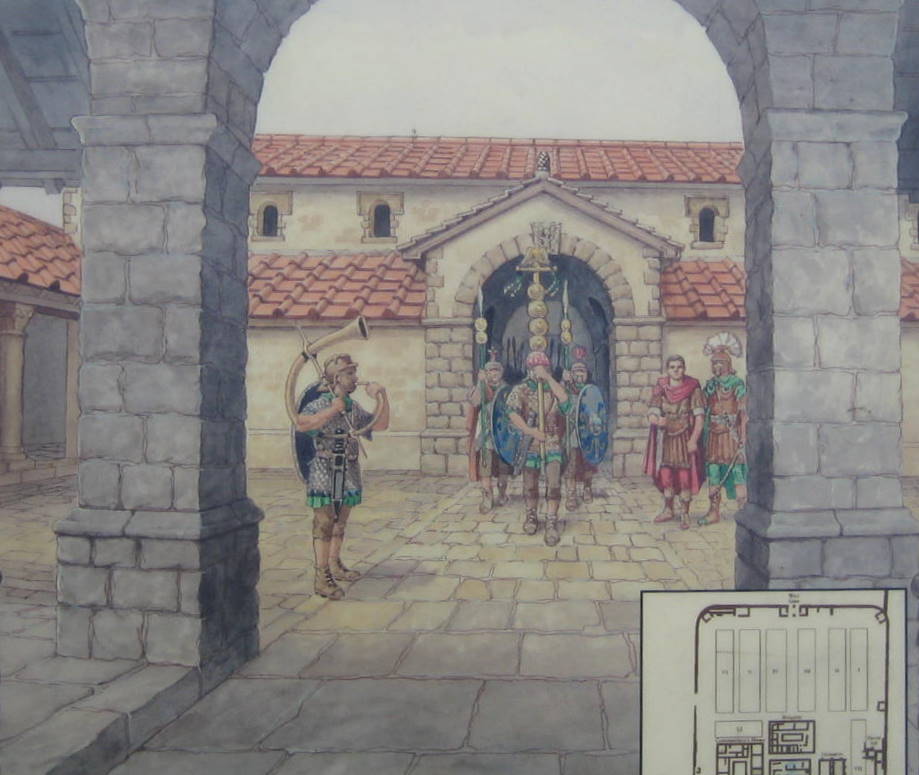

Left and below: diagram and model of the headquarters building in the Housesteads museum. Above: drawing from the site.

We often call the center for Roman affairs the Forum while they use the term principia. In a military camp, the term for their center or headquarters was the praetorium since the head (or Praetor) ran the place from there. The Romans' forts reflected their ordered approach to life, even on the frontier. While they ruled a mostly rural world, their culture was urban. The 5-acre Hallstead's auxiliary fort was laid out like all their others: playing-card shaped with perpendicular and well-spaced streets no matter what the landscape (steeply descending in Housesteads' case). As their headquarters, the praetorium fit well into this overall approach.[19]

|

Left and below: diagram and model of the headquarters building in the Housesteads museum. Above: drawing from the site. |

|

As you can see from the top of the diagram above with the shrine (aedes) in a central -- yet protected -- spot, the praetorium served as both administrative and religious headquarters. Framed by an arch doorway, the shrine served a number of functions including emperor worship (when you have a lot of gods, what's one more?) and storing the battle standards (displayed in action in the drawing upper right). In addition, the paymaster often would have an underground vault under the shrine (but not at Housesteads where the granite Whin Sill made this impossible.) Large Roman camps could mint their own coins but Housesteads was too small for this. However, counterfeit coins and a press were excavated here. Another back room was used as a weapons workshop; a late 19th century excavation found over 800 arrowheads tied up in bundles.[22] The Romans wanted a flexible and interchangeable force: all the soldiers were trained on every weapon (including the officers). In addition, soldiers cycled among the various crafts and clerk jobs so that, in theory, any soldier could be replaced by any other.

|

As you can see, not much is left of the headquarters. We are looking northwest with the granaries on the upper right. In the grassy lagoon at middle right, we see the stubble of three column remnants. These columns once held up the high-ceilinged basilica, the name the Romans used for their administrative and legal building before Christians evolved the term into a description for a large church. This large room contained a raised platform called a tribunal at the far northwest corner where the commandant would dispense justice[20], as it were, on high. (The diagram above labels the basilica as a cross-hall.)

|

Above is another picture of the column that would have been just inside the basilica, leaving a small aisle on the east end. The rightmost stone probably marks the innermost edge of the courtyard. As visitors entered from the Military Road through the east gate, they would travel down the main horizontal road, in any Roman fort called the Via Praetoria (so called because it would end at the Praetorium which would be located on the principle north-south road called Via Principalis). Hence the Praetorium was both the literal and figurative center of the fort and the shrine would be the center of religion, military discipline as signified by the standards, and the Praetorium itself. In fact, when engineers created a camp (either tent or permanent), they would start by placing the headquarters tent in the center and, using 10-foot measuring sticks, lay out the rest of the camp with geometric rigor.

This courtyard once contained sundials used to regulate the changing of the guard shifts.[20] (This was probably a good idea in sunny Italy but at times a challenge in overcast Britain.) Shifts were three hours long and ended with a bugle call. (The drawing at upper right shows the bugle looking a bit like today's sousaphone). In all, the Roman army bugler corps had over 40 different calls to communicate orders to the soldiers.

![]()

This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.