The Barracks

Visited 20 March 2006

The placement of the barracks in a Roman fort evolved

from the position of the soldiers tents when the army was on the march.

Tents faced each other in twin rows 60

feet wide and as long as there were troops to fill the tents. Tents

sardined ten soldiers each in a 10' by 12' space -- each man allocated 10 square

feet. If your kitchen floor has 12" square tiles, see how much room

you'd get. This smallest military unit was known as a contubernium;

today we'd call it a squad. On the march, each squad had a single

tent; during the early days of this fort, a squad had its own room--permanent

housing but still tent sized.

|

|

|

Above and

right: diagrams of two barracks and models from the Housesteads museum.

Upper right: picture from ruins site.

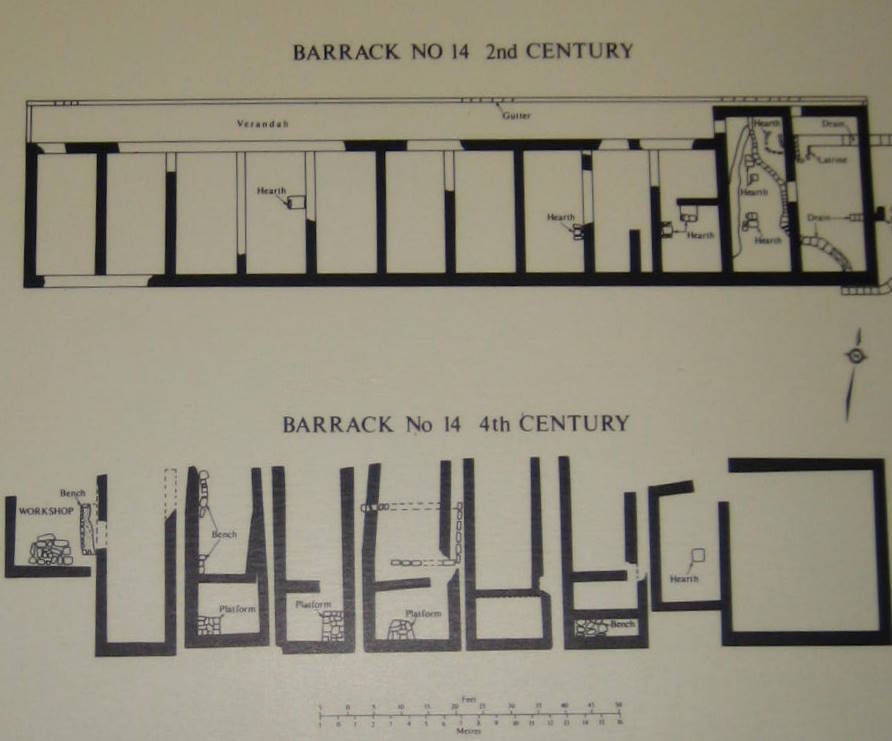

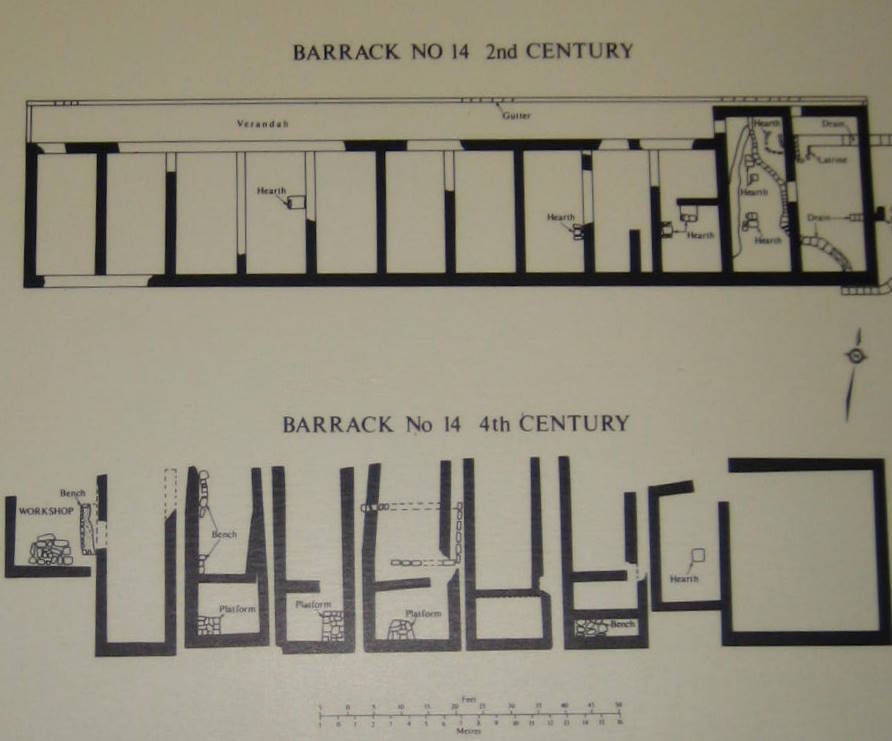

The top diagram shows the barracks as originally built

with a room for each of the ten squads (8-10 men each) with a larger unit

at the end for the centurion who commanded them. While the enlisted

men could not marry, the centurion could have a family and slaves in his

quarters. Barracks would face each other just as the tents did when

the army was on march. By the 4th century (lower diagram), barracks

had evolved to individual small dwellings with individual roofs.

Possibly this meant that soldiers were allowed to have families who had to

live inside the fort for security against a growing external menace as

Roman rule deteriorated.[15]

Before then, enlisted men could not have wives, at least

living with them. |

|

|

It takes a bit of extrapolation to get from here to the

rows of stones excavated on the rising hill (see below). However,

one can make out the pattern of individual buildings.

|

Let's talk a bit more how the form latent in these stones followed the

function of the army organization:

|

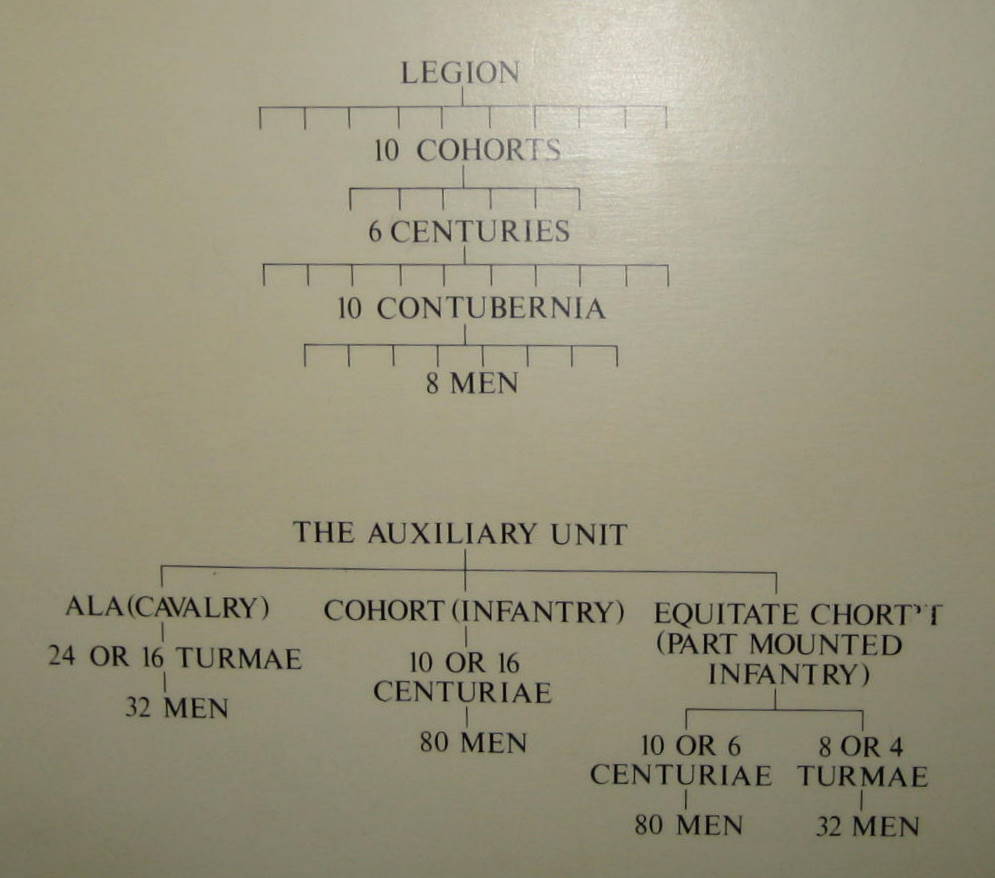

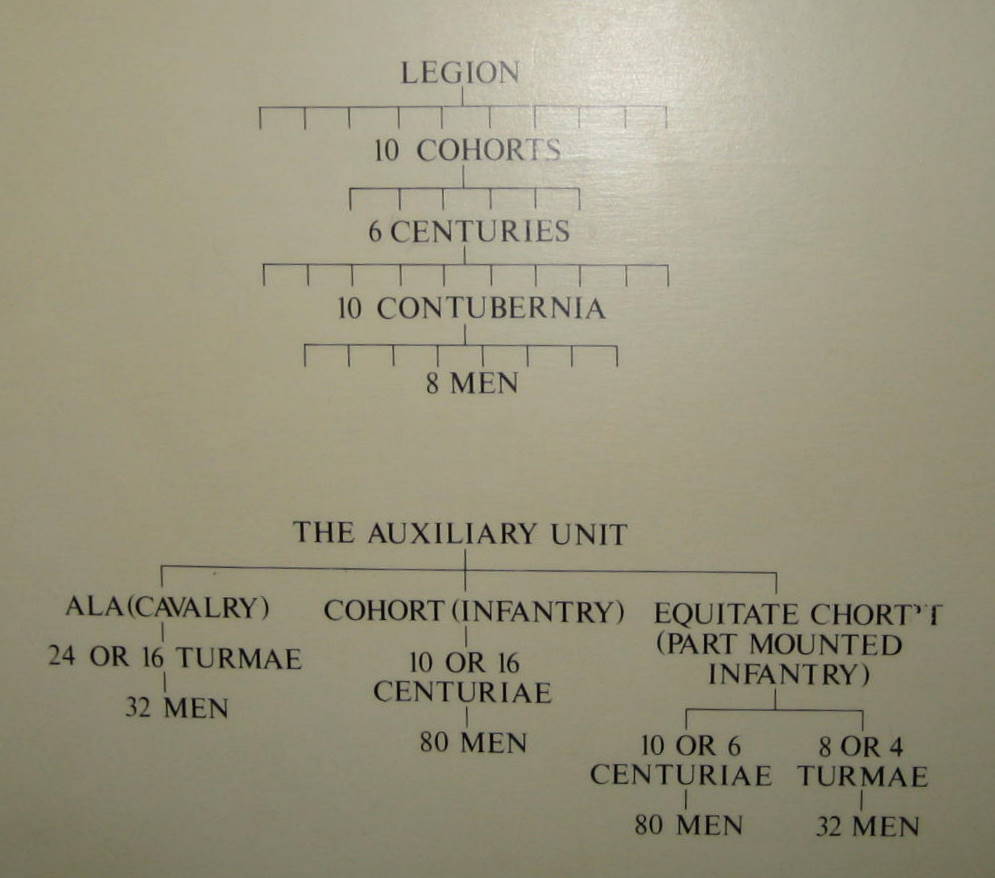

At right is a diagram of the structure of the Roman army

as displayed in the Housesteads museum. The "A" team, the

legionnaires, are at top. These were Roman citizens who served 16

year stints (which could be extended.) They did the heavy lifting

such as leading in wars and building forts such as Housesteads.

The lower section diagrams the auxiliary units.

These were typically soldiers from provincial tribes. They became

Roman citizens upon discharge. Typically they all came from one

province and would serve in different area -- so their allegiances would

be to the army, not to the people of the area. At Housesteads, the

auxiliary unit came from Belgian.

The smallest unit was the squad, called the contubernium.

These would have a room in the barracks (or a single tent when on the

march). The math is a little funny as you would expect a

century to have 100 men. It had only 80 fighters as each

contubernium would have 8 soldiers and 2 support personnel to bring water

and tend to the mules. Squad discipline was on a group

basis. If anyone failed, all in the contubernium

would draw straws; he with the shortest straw would be stoned by his

fellow squad members. Quite an in-tents situation. |

|

The Romans weren't dumb! Studies

of the Iraq and other modern wars have shown that soldiers fight for each other.

Unit cohesion is essential to military success. And don't think the mules

made life that much easier. A squad would typically have only one

mule. To avoid the logistics of having long trains of mules supplying the

troops, soldiers on the march were expected to carry 50-60

pounds on their backs (remember, they were smaller people in those days so

this typically meant half their weight) plus special tree branches to contribute

to a fence around an emergency fort that could be set up in the heat of battle

under the direction of specially trained engineers.

|

Here's a parting shot of the barracks area (and a few other topics).

Somewhere in here was also a Roman bath. In this case, it was a large

building with a massive roof used to collect rainwater to be used inside the

bath. Water was a big problem at Housesteads. The fort was located

here because of the water supply in a nearby creek called Knag Burn. Rain

water runoff was channeled from the roofs into ditches which could then be

routed through the latrines downhill. (In essence, the toilet was always

flushing). Water tanks also held excess rain water. These would be

made of stones and sealed with lead. That may work for sewers, but lead

creates problems with drinking water; some scholars think Rome's slow poisoning

of its brains through lead contamination

contributed to its downfall. Although inconvenient, there's some debate

over this truth. Should we say "all pipes are lead in Rome"? How

long has technology had unintended

consequences?)

Created on 15 October 2006

This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.