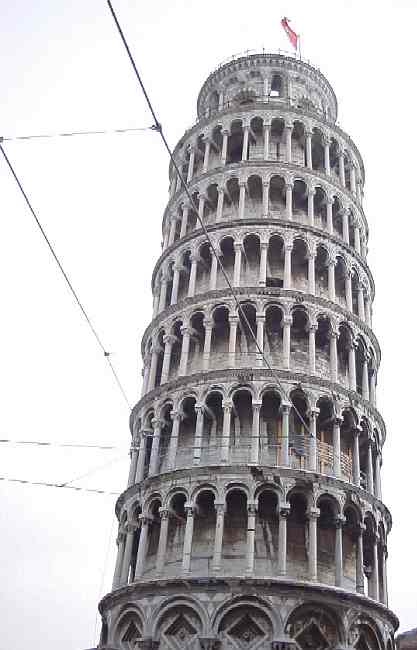

OK, why are we so fascinated by this fiasco? Pisa's beautifully ornate tower tilts almost 10% (17 feet) off center -- and could crash down like Venice's tower did in 1902 or Pavia's only 10 years ago. It reminds us that many medieval buildings failed. Besides the tilt, the tower could break apart from excessive twisting forces first! Sitting in the middle of an earthquake belt, Pisa's bell tower has somehow survived 800 years. For the last ten of those, it has been off limits for visitors, including us. This gives us reason to rant since we don't have enough pictures to fill up this page.

Medieval towns were on a tower trip much like second rate American cities develop fetishes for NFL franchises. The bigger your tower, the more prestige you had. (I know, sounds like a guy thing. In fact, Fascist leader Benito Macho-lini in the 1930s decided that Pisa's tower was an inappropriate icon and ordered his inept engineers to straighten it out. They dumped nearly a 100 tons of concrete around it and it tilted even more.) Pisa may not be a world player today, but in the 12th century it was in the major leagues, kicking Saracen butt in Sicily, colonizing the Mediterranean, etc. And so it was natural that they would start the world's most ornate bell tower near its look-alike cathedral. But being a maritime power meant Pisa was near the ocean, too near as the few miles between them and the shore is soft alluvial marsh. Unknowingly, the tower was placed on the ancient site where the Arno flowed into the sea.

After two grand Pisan Gothic successes in building the Cathedral and Baptistery, the Pisans were humbly reminded that medieval engineering was still not a science but more of an art (and one highly dependent upon luck). In 1173 it would still be 600+ years before con artists would invent Houston and so the masters of subsidence and shallow foundations were building in Pisa instead of the Texas Gulf coast.

Using standard soil analysis, today's engineers would tell these 12th century builders that the weight of the tower was 10 times what the sandy soil could hold. Consequently, THE TILT began within the first five years of building with only three levels completed. The Pisans then let a century go by hoping that everything (soil and tower) would "settle." Today's Italians continue to think that time will miraculously heal their decaying architecture, but let's not go into that again.

Around 1275 three more levels were added with the stone elongated on some sides to compensate for the tilt, giving the tower a slight banana shape (does this explain its appeal?). The belfry capped off the structure in the 14th century. Since then it has withstood earthquakes and the American bombings of the area during WWII -- but gravity has slowly tipped it more closely to the ground until it has reached today's critical state.

But the problem is more complex than gravity. In fact, the subsidence is not consistent and so THE TILT has changed directions at least three times, putting tremendous twisting motion on masonry that usually holds up well enough with the compressed vertical pressures of height. To make matters worse, for all the thickness of its walls (8 feet or more at the bottom), the tower is essentially two thing marble cylinders filled with mortar and rubble--but inconsistently so and without the marble strongly fusing the ingredients into a solid unit. This means that thin marble has to bear pretty much the full weight of the tower. So some parts of the building are threatened by structural failure even if the rest of it doesn't tip over first.

Because of the danger, the tower was closed so we couldn't get to walk inside. (If you want a good walk up the stairs, your body scraping the sides because of the slant, try this link).

The Italians started solving their engineering problem with the ultimate American solution -- a committee -- coupled with the typical Italian solution -- no money. Today's is the 15th committee meant to save the tower -- this century. Hopefully this time they will succeed. To start, they funded a great photo study to record the tower in detail through 6400 pictures, including interactive video. If you've got good bandwidth and some curiosity left, try: http://torre.duomo.pisa.it/index_eng.html

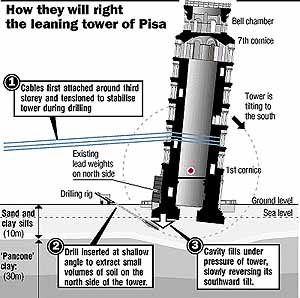

| From what I've been reading in the papers, thanks to British soil specialist John Burland the tower correction is in progress and it will reopen in 2001. (Closed in 1990, the work was to have taken three years; part of the problem seems to be that the ever changing Italian government was slow to fund the $7M it took to do the work--about what Americans used to pay for a toilet seat on an aircraft carrier before they put a lid on such spending). The current solution entails drilling soil out from underneath the high north side of the foundation, letting the remaining soil gradually fill the hole like quicksand. (It took a computer model to figure that out!) |  |

To avoid the perhaps imminent collapse during construction, engineers have created a really ugly temporary solution -- but not as ugly as the scaffolds that would hide the ornate galleries of the tower. On our visit, the tower's fragile second story was wrapped with ten plastic coated steel support bands, something like braces on Claudia Shiffer's teeth (OK, what will she look like in 800 years?).

A hundred yards to the north, hidden behind smaller buildings near the square, these bands are anchored by long cables to muscular horse necks:

In addition, the foot of the tower now temporarily hosts 800 tons of lead, trying to further stabilize the tower until the repairs can complete.

The early work has been somewhat successful. Last Christmas the three largest bells were reactivated as their vibrations were no longer a threat. (There are seven bells in all, tuned to the scale so if you know any 3 note Christmas carols, let them know). Another Christmas gift: the great storm of December 1999 that hammered Western Europe moved the tower another millimeter with its 70 mph winds, but the building sprung right back afterwards. So maybe these steps are working. If they do, the tilt should be slightly corrected and 300 years added to the life of the tower. Maybe the Japanese will return -- 90% fewer of them come each year now that the tower is closed. Maybe the Italians will learn that they cannot afford not to maintain their marvelous past as 30% of Pisa's economy comes from the tourist industry.

Ironically the tower, perhaps the world's best known (or at least prettiest) engineering mistake, is also a shrine to practical science: Atop this tower in 1590 a local university math professor conducted gravity experiments which made him challenge Aristotle's approach to science (think first, then don't experiment). Because Galileo dropped his balls from the tower, experimental science eventually gave architects the tools to keep most buildings from falling over. For us moderns, the word is most. Modern engineering can give us hideously ugly buildings that can still fall down, including the world's 7th tallest building built about 20 years ago. At least the Medieval bulders gave us beautiful failures. If you're in a profound mood, try this link. If you're in a religious mood, pray that this church bell tower stabilizes soon.

Or if you're in a macabre mood, join us as we next visit the Cathedral's indoor graveyard. It's not as morbid as it seems and this place is pretty much unknown unless you've visited Pisa. Please join us by clicking here.

Here's a great site about the tower that you should visit if you are at all interested in this building. Click here.

Where do you want to go today? Here's a few choices: